|

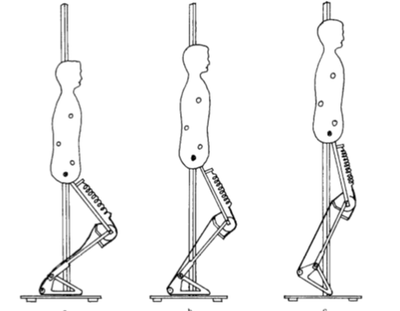

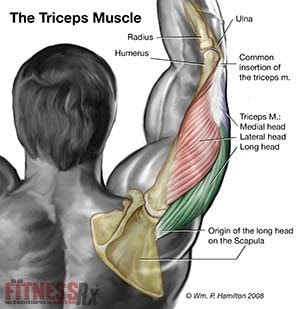

In a previous article (A Case for Quads), I wrote about the relationship between single-joint muscles (quads, glutes) and their antagonist counterparts that cross two joints (hamstrings, rectus femoris, calves). In movements where the two-joint muscles lengthen at one end and shorten at the other (like the hamstrings during a squat), the muscle does not contract fully, but rather maintains a similar length throughout the entire movement. If we use a thought model that replaces two-joint muscles with rigid strings, we find that as the single joint muscle contracts to extend its joint (say, quads extending the knee), slack gets taken out of the antagonist two-joint 'string' (calves in the example below) and causes extension at the opposite joint (ankle). The spring (quadriceps) actively shortens, causing the knee to extend. This causes slack to be taken out of the string (calves), causing plantar flexion. Simply put, quads aid in hip extension via the hamstrings, glutes aid in knee extension via the rectus femoris, and the quads again aid in plantar flexion via the calves. Since the quads and glutes contract throughout the entirety of the movement, these single joint muscles can be thought of the work horses of squatting and jumping; the move the system as a whole while the two-joint hamstrings and rectus femoris work primarily to maintain position. This is consistent with general training wisdom that prescribes squats as a primary builder for the glutes and quads, but not necessarily the hamstrings. In fact this article by Greg Knuckols discusses a study that showed world class squatters having a higher quad/hamstring strength ratio than their lower-tier competitors. Here we can see where the long head of the tricep crosses the shoulder joint to attach to the scapula. In a bench press, the long head shortens at the elbow, but LENGTHENS at the shoulder joint, just like the hammies in a squat. Since the upper body is also made up of single-joint muscles with two-joint antagonists, pressing movements can be thought of in similar terms. The pectorals are a single joint group that originate in the center of the sternum and attach to the humerus, acting solely to adduct the upper arm. The triceps are made up of three heads, the biggest of which (the long head) crosses both the elbow and shoulder joint. Similarly to the two-joint muscles of the lower body, the long head of the triceps shortens at the elbow during pressing while simultaneously lengthening at the shoulder, while the pectorals contract during the entire movement. Hold your arms in front of you as if you were at the top of a bench press and squeeze your triceps as hard as you can. Now, maintain that tension while moving your arm down and back, as in doing a pressdown. You should feel the contraction in your tricep intensify. This is because peak contraction in the tricep occurs when the elbow is extended AND the shoulder is abducted; one of the reasons pressdowns and kickbacks done for high reps are so devastating. Because the long head of the tricep does not fully contract during a bench press, we can apply the 'string' model from above. The same action occurs as in the lower body; the pectorals (and delts) act to move the upper arm and slack gets taken out of the long head of the triceps, causing it to extend the elbow. Just like the hamstring/quad relationship in a squat, the long head of the triceps causes elbow extension by maintaining position across both joints while the pecs act to move the ENTIRE system. It just so happens that the mid-point of a bench (the sticking point that often gets credited as a 'lockout weakness') is also where the pectorals are the most disadvantaged. When the bar is on the chest, the elbows are generally tucked (improving leverage on the upper arm) and mechanical tension is created by the pecs being stretched and the lats and biceps being compressed against their respective joints. This is why most lifters can typically clear some distance off their chest, even with loads that are way above a reasonable one-rep-max. When the bar gets closer to the mid-point, the mechanical tension is lost and the elbow moves further out, away from the shoulder joint, worsening leverage. So if the pecs can be said to carry the system as a whole, and they are most disadvantaged as the bar moves off the chest towards the mid-point, it is entirely possible on a missed attempt that it is the pecs that weren't up to snuff rather than the typical talking point, which puts blame on the triceps. By no means am I suggesting that the triceps can take a back seat when developing a big press. The lateral and medial heads only cross the elbow joint, making them solely responsible for extending the elbow. And the pectorals' ability to move the entire system is only as good as the triceps' ability to maintain position across the elbow and shoulder. What I am suggesting is that there is an epidemic caused by modern 'powerlifting' protocols. Top end work like slingshot, board, and floor presses (and don't forget about the bands and chains) are overemphasized to fix weak points when a little bit of old-school medicine would have done the trick. The best raw benchers, by a wide majority, have historically included numerous sets of bodybuilding work to build up the pecs. Strong pectorals are the result of a high volume of focused work; paused, wide grip, and dumbbell variations for multiple sets at a variety of rep ranges and, yes, even flys and crossovers. This focused work is strangely absent from the IG feeds of amateur lifters. When pec work is prioritized, several things will happen rather quickly: 1.) Control and stability at the bottom point of the lift will increase dramatically. When the pecs are pulling their weight, precision improves and it feels like you are benching on a cloud. The shoulder joint tends to appreciate this. 2.) Starting speed will increase dramatically. Stronger pecs mean a more aggressive initial push off the chest. More starting speed equals greater momentum, which means a higher likelihood of pushing through previous stick points. 3.) You will begin to look like you workout. Everyone pretends like this is a distant second to moving weight, but, to paraphrase Doug Young: "Anyone who says they want to be strong without looking strong ain't telling the whole truth."

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed